|

|

|

WALKING AND BIKE TOURS

Discover London walking or biking. We have short 1.5 hour tours and longer tours up to 4-5 hours covering more ground and more of London's history, iconic attractions and vibrant multicultural areas at the cutting-edge of cool.

Click here to review what's on offer. |

|

Exploring & Touring London

Another area of London to explore and experience. Click back to Touring London.

|

| Exploring London's Art Deco Architecture |

Walking Art Deco London

by Andrew Reid (London, May 2003)

PART ONE:

Start: Oxford Circus Tube Station

Finish: Piccadilly Circus

INTRODUCTION: London in the Art Deco period was a city undergoing strong currents of change and trauma. It was an era of both hope and great anxiety. It was marked by political strife and some social progress. It was a time of obscene inequality and class war as well the occasion of the first ever Labour cabinet. Imperialism and racism were the mainstay of politics. Whilst most of the Deco architecture, such as the hotels and offices, was built for the rich, over a million Britons continued to live in appalling Victorian slums. Some of the new building was more egalitarian however, and included public works, notably in transport with the founding of London Transport.

The Deco era spans two decades; the twenties and the thirties, a sandwich between one horrific, devastating war and another. It was an era which saw the end of British rule in Southern Ireland, the General Strike, the Wall Street Crash, the Jarrow Marches, the rise of Oswald Mosley and his gang of British Fascists, the abdication of Edward the Eighth and his subsequent marriage to Wallis Simpson. It was an age that went from the jubilant degradation of Germany to the appeasement of Hitler by a British government. It was also a time of cultural flowering. It was the time when Hollywood was the centre of a glamorous imaginary world of beauty and riches; Greta Garbo, Laurel and Hardy, and Marlene Dietrich graced the new silver screen. In literature London was home to the Bloomsbury set, PG Wodehouse and Evelyn Waugh. In fashion, the 'flapper' became a symbol of hip, with pearls, tight helmet like hats and daringly high skirts. In music, Jazz flourished, as did the songs of Noel Coward.

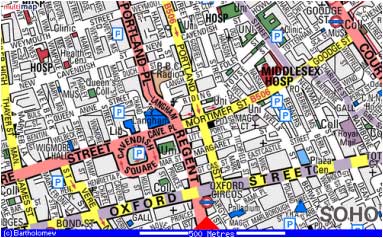

We begin our walk at Oxford Circus tube station. Take the Argyll Street exit. On Argyll Street note the outstanding black Art Deco building. This is Palladium House, also referred to as Ideal House or the National Radiator building. It is a gorgeous black granite clad building, with exotic Moorish-Persian style enamel on bronze polychrome, by the Birmingham Guild of Handicraft. Built in 1928 by Raymond Hood and Gordon Jeeves, it is similar to the Daily Express building (Fleet Street) by the use of black walls and was also known as the Moor of Argyll Street. It is an exuberant and exotic fantasy, a tantalizing taste of Babylon in London. At its base it is square, disciplined and masculine yet flowering in an extravagant fantasy on the top floors. Note the yellow surrounds of the doors and windows on the ground floor, which blend yellow, orange and green tiles into a floral motif. Next door in Argyll Street is the London Palladium theatre where the Crazy Gang, a collection of comedians led by Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen used to play to packed audiences in the 1930s. Another form of entertainment that became widespread in the thirties was busking, as musicians arrived in London from the four corners of the British Isles in search of a living. Many buskers were Welsh, part of the mass emigration of over a half a million Welsh people during the Depression. Note the interesting building known as Lyndall House, a few dozen meters from the Palladium, along Great Marlborough Street at 49-50. It is a five-floored building with a stone facade on the ground floor and first floor but with small, rectangular bricks, punctuated by three windows on the rest of the floors. It is reminiscent of the Amsterdam School of architecture. During opening hours, it is possible to enter our next point, Marks and Spencer's, through the rear entrance. If not return to Oxford Street and turn right.

We begin our walk at Oxford Circus tube station. Take the Argyll Street exit. On Argyll Street note the outstanding black Art Deco building. This is Palladium House, also referred to as Ideal House or the National Radiator building. It is a gorgeous black granite clad building, with exotic Moorish-Persian style enamel on bronze polychrome, by the Birmingham Guild of Handicraft. Built in 1928 by Raymond Hood and Gordon Jeeves, it is similar to the Daily Express building (Fleet Street) by the use of black walls and was also known as the Moor of Argyll Street. It is an exuberant and exotic fantasy, a tantalizing taste of Babylon in London. At its base it is square, disciplined and masculine yet flowering in an extravagant fantasy on the top floors. Note the yellow surrounds of the doors and windows on the ground floor, which blend yellow, orange and green tiles into a floral motif. Next door in Argyll Street is the London Palladium theatre where the Crazy Gang, a collection of comedians led by Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen used to play to packed audiences in the 1930s. Another form of entertainment that became widespread in the thirties was busking, as musicians arrived in London from the four corners of the British Isles in search of a living. Many buskers were Welsh, part of the mass emigration of over a half a million Welsh people during the Depression. Note the interesting building known as Lyndall House, a few dozen meters from the Palladium, along Great Marlborough Street at 49-50. It is a five-floored building with a stone facade on the ground floor and first floor but with small, rectangular bricks, punctuated by three windows on the rest of the floors. It is reminiscent of the Amsterdam School of architecture. During opening hours, it is possible to enter our next point, Marks and Spencer's, through the rear entrance. If not return to Oxford Street and turn right.

Continue as far as the corner of Poland Street where you will come across the black Marks and Spencer (right) building at number 173, otherwise known as the Pantheon. Note the simple windows set back into the faŤade. Next door at number 175 Oxford Street note the almost Bauhaus quality of the faŤade, with the curving above the top window. From here we cross Oxford Street and turn right into Great Titchfield Street until the corner with Market Place. Here we can admire the New York style Art Deco pile of Kent House. Continue along Great Castle Street and into Regent Street where we turn right and up to Langham Place where we discover Broadcasting House. This is an example of the 'ship' trope common in many Deco buildings, with its prow cutting into the street. It has a Modernist simplicity and is decorated with statues by Eric Gill and Vernon Hill. The building was completed in 1932 on the site of an 18th century manor house. The hall area is spacious and light but the rest of the building is out-of-bounds. Return as far as Cavendish Place. Turn into Cavendish Square and then into Henrietta Place. Continue as far as the corner of Poland Street where you will come across the black Marks and Spencer (right) building at number 173, otherwise known as the Pantheon. Note the simple windows set back into the faŤade. Next door at number 175 Oxford Street note the almost Bauhaus quality of the faŤade, with the curving above the top window. From here we cross Oxford Street and turn right into Great Titchfield Street until the corner with Market Place. Here we can admire the New York style Art Deco pile of Kent House. Continue along Great Castle Street and into Regent Street where we turn right and up to Langham Place where we discover Broadcasting House. This is an example of the 'ship' trope common in many Deco buildings, with its prow cutting into the street. It has a Modernist simplicity and is decorated with statues by Eric Gill and Vernon Hill. The building was completed in 1932 on the site of an 18th century manor house. The hall area is spacious and light but the rest of the building is out-of-bounds. Return as far as Cavendish Place. Turn into Cavendish Square and then into Henrietta Place.  From Henrietta place, turn immediately into Old Cavendish Street and then go to the corner with Oxford Street. Here we should admire the very distinctive House of Frasier (left) which takes up a corner block. Note the white, stone facade, the curved periscope-like pillars, and the uniform black-edge windows. From Henrietta place, turn immediately into Old Cavendish Street and then go to the corner with Oxford Street. Here we should admire the very distinctive House of Frasier (left) which takes up a corner block. Note the white, stone facade, the curved periscope-like pillars, and the uniform black-edge windows.

Cross over Oxford Street and note the black-tiled faŤade of the former HMV store at 363 Oxford Street. Opened by Sir Edward Elgar in July 1921, it is a very distinctive building. Note how the black-tiled floors are sandwiched with layers of thick glass tiles. The store is now known as Footlocker. Continue along Oxford Street as far as Selfridges, on the north side of the road. Selfridges is one of the jewels in the crown of Art Deco London. Whilst the original building was completed in 1909, much of the interior was completed in the twenties in Art Deco style. It was exceptional for being one of the largest, and the first steel-framed buildings in Britain. Its open-plan interior was also unusual and shoppers were transported upstairs in Art Deco lifts. These have long since been replaced but are happily preserved at the Museum of London. Outside the Classical decoration was designed by Francis Swales. There were plans for a giant central tower that never came to fruition. Note the huge statue above the doors, the Queen of  Time, supporting a clock on her shoulders. She is positioned on a concrete ship's bow, like so many Art Deco structures cutting through an imaginary sea. American citizen Gordon Selfridge caused quite a stir when he fell for both of the Dolly Sisters, who were cabaret artists and socialites. Between 1924 and 1931 he spent an astronomical amount of money on them and allowed them virtually unlimited access to his shopping emporium. Time, supporting a clock on her shoulders. She is positioned on a concrete ship's bow, like so many Art Deco structures cutting through an imaginary sea. American citizen Gordon Selfridge caused quite a stir when he fell for both of the Dolly Sisters, who were cabaret artists and socialites. Between 1924 and 1931 he spent an astronomical amount of money on them and allowed them virtually unlimited access to his shopping emporium.

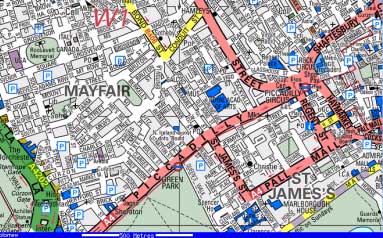

Cross Oxford Street and continue along Balderton Street. Note the Art Deco-style Avis garage, with its slightly Egyptian columns set in a white stone facade. Continue into Grosvenor Square where you turn left. Continue along Grosvenor Square until you come to Brook Street. Follow Brook Street to the corner of Davis Street. Here we find our next Art Deco gem Claridge's, on Brook Street. Originally a Victorian butler, William Claridge saved enough to buy a small hotel on this site. Several expansions and modernisations saw it become the 189-bedroom luxury hotel it is today. Note the Deco lamps and the marble floors. Claridge's has the romance of by-gone era and is a wonderfully decadent place to drink and listen to the piano or to enjoy afternoon tea. One could imagine Bertie Wooster entertaining some fearful aunt here or a Barbara Cartland heroine coming out. Continue along Davies Street to Grosvenor Street where you turn right. Follow this road straight through the south side of Grosvenor Square and along Upper Grosvenor Street till you get to Park Lane where you turn left. This will bring you to Park Lane. At the corner you will come to the Dorchester Hotel (right), built in 1931 using a curved structure and designed by Sir Own Williams and with sculptural friezes and balconies added by W. Curtis Green.

Continue down Park Lane and use the underpass to get to the central island at Hyde Park Corner. Make your way to the large statue nearest the park. In 1925 Charles Sargeant Jagger's memorial to the Royal Artillery was unveiled at Hyde Park Corner. Note the bas-relief. The bas-relieved tries to convey human spirit in face of conflict and adversity. Leaving the island we make our way onto Piccadilly and continue as far as the Sheraton Hotel. This hotel is an Art Deco gem and if you have the opportunity go inside to experience the wonderful furnishings. At 110a, we find the imaginary site of Lord Peter Wimsey's home. This aristocratic dandified sleuth of the Deco period, whose very name hints at aimlessness and privilege, was created by Dorothy L Sayers. In this popular 1920s series of novels we learn that Wimsey was born in 1890, to an ancient aristocratic family. He was a sickly child, unhappy at school, educated at Eton and Oxford. He served as a major in the Rifle Brigade and was a member of the Marlborough Club. He was unhappy in love during the war which made him reckless, and in 1918 he was blown up and  suffered a breakdown. He moved into the Piccadilly flat with 'the man Bunter', his former sergeant. This living arrangement of bachelor/man-servant is of course similar to Bertie Wooster. Like Wooster, Lord Peter Wimsey was a man who didn't need to work. He was frivolous, and emotionally stunted with a 'dilettante pose.' One can visualize such men, in tuxedos and spats, smoking and quaffing champagne at the nearby Ritz. They were decadent and parasitical, a million miles from the reality of poverty and grime that blighted other parts of London. suffered a breakdown. He moved into the Piccadilly flat with 'the man Bunter', his former sergeant. This living arrangement of bachelor/man-servant is of course similar to Bertie Wooster. Like Wooster, Lord Peter Wimsey was a man who didn't need to work. He was frivolous, and emotionally stunted with a 'dilettante pose.' One can visualize such men, in tuxedos and spats, smoking and quaffing champagne at the nearby Ritz. They were decadent and parasitical, a million miles from the reality of poverty and grime that blighted other parts of London.

As any Wodehouse fan should know, Half Moon Street, just off Piccadilly, is the site of Bertie Wooster's flat, which he shared with his gentlemen's gentleman Jeeves. Bertie Wooster is a definite product of the Deco period. Wodehouse first created him in an initial installment to the Strand magazine in 1933. Wooster is a drone, an aimless and privileged young man who is lucky enough to not need to work. He is under the heel of a couple of awesome sounding aunts. Wooster is helpless and is utterly dependent on the intelligence and cunning of Jeeves, who seems to act in loco parentis. Jeeves travels to that capital of the Deco style, New York on a couple of occasions, travelling on the highly glamorous Art Deco ships of the era. Cross the road just by the underground station at Green Park. On the south side of Piccadilly is the Ritz, one of the most prestigious hotels in London, which has something of a Deco feel, especially its Orient Express style bar. It was to the Ritz that the young upper classes flocked during the Roaring Twenties, for balls and dances a la Barbara Cartland. It was also a popular watering hole of Evelyn Waugh. A few doors along Piccadilly is China House,(right) a grade II Art Deco listed building. Now a Chinese restaurant and bar, China House was formerly the show rooms of Wolseley car company. It was designed by William Curtis Green, the same man who designed the Dorchester, and opened in 1922. This is an incredible building and you can enter here to enjoy a drink or meal in fabulous Deco surroundings.

Further along Piccadilly at number 203-206, we come to Waterstones, (left) the largest bookshop in Europe. It is a gem of thirties architecture, with a  Modernist feel. It was formerly the Simpsons clothes store, which is said to be the Grace Brothers of the seventies comedy series Are You Being Served. Of note here are the exceptionally low and potentially lethal banister rails. The lifts are also unusual. Check out the rooftop bar. At the end of Piccadilly we descend the steps into Piccadilly Tube Station, built in the Twenties and with Deco overtones, shared with many London Underground stations. The Underground expanded during the twenties and the glamorous Deco style fitted the bill, with elements of travel, movement, internationalism, streamlining and modernism. Frank Pick, the chief executive of London Underground during the era, had the vision to create the world's finest integrated transport system. Charles Holden, a red-haired, vegetarian, teetotal Quaker, was behind the design of the stations in the twenties and thirties. He was offered a knighthood on two occasions and refused it both times. In 1923 Pick and Holden joined forces to embark on the project and much of this work can be seen by hopping on a train here. Some of the tube stations are curvy such as Arnos Grove. Others are single turreted brick buildings, not unlike Hilversum Town Hall in the Netherlands, for example Boston Manor. Holden was much impressed by the work of Dudok on a visit to the Netherlands. At some point try and see Osterley and Park Royal stations as well. Modernist feel. It was formerly the Simpsons clothes store, which is said to be the Grace Brothers of the seventies comedy series Are You Being Served. Of note here are the exceptionally low and potentially lethal banister rails. The lifts are also unusual. Check out the rooftop bar. At the end of Piccadilly we descend the steps into Piccadilly Tube Station, built in the Twenties and with Deco overtones, shared with many London Underground stations. The Underground expanded during the twenties and the glamorous Deco style fitted the bill, with elements of travel, movement, internationalism, streamlining and modernism. Frank Pick, the chief executive of London Underground during the era, had the vision to create the world's finest integrated transport system. Charles Holden, a red-haired, vegetarian, teetotal Quaker, was behind the design of the stations in the twenties and thirties. He was offered a knighthood on two occasions and refused it both times. In 1923 Pick and Holden joined forces to embark on the project and much of this work can be seen by hopping on a train here. Some of the tube stations are curvy such as Arnos Grove. Others are single turreted brick buildings, not unlike Hilversum Town Hall in the Netherlands, for example Boston Manor. Holden was much impressed by the work of Dudok on a visit to the Netherlands. At some point try and see Osterley and Park Royal stations as well.

Part two

|

|

|

|